Think about the images that you love. Maybe it’s Baby Yoda with his soup bowl. The Andy Warhol Campbells can. Any sequence from 2001: A Space Odyssey. These images come from wildly different contexts, but they have something in common: they have appeal.

What is appeal? While you might not have a precise definition, you probably know it when you see it. Appealing images draw viewers in, and creating appeal is key to making art people love.

Whether you sketch in your free time or want to understand what artists do, appeal is a great place to start. Its fundamentals are intuitive and applicable to anything you'd like to design or draw.

Expert Insights on Appeal

We spoke with Archer Dougherty and Casey Robin, two Laetro artists with extensive experience in animation, illustration, fine art, character design, and visual development. They share essential principles for creating appealing art.

Appeal: the key to drawing things people love

Understanding the Essence of Appeal

At its core, appeal is the charismatic quality that makes an image or character impossible to ignore. It captivates and engages, ensuring that viewers remain entranced. Importantly, appeal extends beyond conventional beauty; it encompasses a broader spectrum that includes even the most villainous characters, such as Jafar or Coraline's Other Mother. Despite their sinister nature, these characters possess an allure that commands attention.

According to Casey Robin, an award-winning animator and illustrator with credits at Pixar and Disney Animation Studios, appealing images resonate with viewers because they tap into fundamental human instincts. "Appealing images exhibit a harmony of shape, color, and form," she explains. "They present patterns that are inherently recognizable, allowing us to intuitively grasp the visual cues. Yet, they also introduce an unexpected twist to these familiar patterns, creating a dynamic balance."

The concept of appeal has a rich historical lineage, with artists and designers throughout history studying patterns and proportions that humans naturally find pleasing. The Golden Ratio, for instance, is a classic example. While mastering these techniques requires technical expertise, you can develop an eye for appeal by keenly observing images that captivate you and analyzing their shapes and colors.

Key Concepts in Creating Appeal

What Makes Art Appealing?

- A magnetic quality that makes artwork impossible to ignore

- "Screen presence" that keeps viewers engaged

- Impact beyond beauty (even villains can be appealing)

- The essential ingredient that makes artwork memorable

Why Appeal Works

- Taps into human instincts

- Built on recognizable patterns

- Combines familiar elements with unexpected twists

- Creates harmony through shapes, colors, and repetition

- Rooted in ancient design principles

Expert Insights from Casey Robin

- Seek harmony of shape, color, and form

- Use recognizable patterns as foundation

- Add dynamic twists for interest

- Balance familiarity with surprise

Getting Started with Appeal

No formal training needed – build your skills by:

- Observing what draws your eye

- Studying shapes and colors in everyday life

- Noticing recurring patterns

- Practicing regular observation

- Trusting your developing instincts

Every character needs a context

The Importance of Context

Every character in a visual narrative requires a context to truly come alive. While shapes and proportions form the technical foundation of appeal, the creative exploration of a character's environment is equally vital. This is a skill that anyone can cultivate through practice and research.

In crafting a visual story, character development typically takes center stage. However, it's crucial not to create characters in isolation. Consider the creative process behind Pixar's "Toy Story." The artists didn't develop Woody in a vacuum and later place him in Andy's room. Instead, the most compelling stories emerge when characters and their environments evolve in tandem.

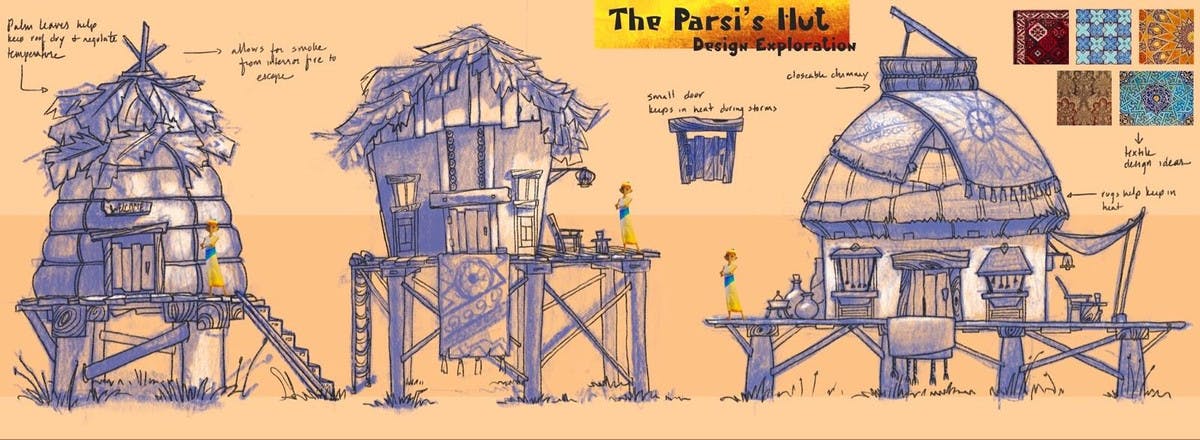

Archer Dougherty, a visual development artist with over 15 years of experience in animation and fine arts, emphasizes the importance of holistic appeal. "The secret to holistic appeal is to create the character and their environment so that they are inseparable," she explains. "Each element would be diminished without the other."

Creating the Right Environment

"The character's environment should reflect their psychological state," Archer explains. "Stories take the protagonist on a journey with an emotional arc, and their environment should reflect those changes."

Consider Carl from Pixar's Up – his house physically manifests his emotional state. Stuck in the past after his wife's death, his fading, antiquated house mirrors his inner world. Only when he embarks on his adventure with Russell does his environment brighten with youthful colors as he rediscovers joy.

Creating rich environments requires cultural, historical, and demographic research. When drawing a piece set in a specific culture or time period, study the shapes, colors, textures, and materials common to that setting.

Drawing from Nature

Every drawing starts with basic shapes. "I always start with a circle," says Casey. Carl from Up is based mostly on rectangles. Nature provides the best inspiration for these foundational elements.

All art stems from nature. Artists process the world through their perspective and share what they see. "Nature is a better designer than you are," Casey tells her students. "When you draw from nature, you'll discover color combinations you've never imagined."

Practical Tips for Nature-Inspired Art

- Observe your surroundings mindfully

- Study natural color combinations

- Build a mental library of shapes and patterns

- Apply these elements in your work

At Laetro, we believe ideas are living creatures. "When I draw fairies on Instagram Live," says Casey, "I start with the largest element, like the water lily the fairy rests on. I study its shape, then ask: Where is the fairy? How is it made? The natural shape of the lily guides the fairy's design."

Starting Your Creative Process

The creative process often begins with broad strokes, gradually refining details. "You wouldn't begin sewing a wedding dress by embroidering the lace," Casey notes. Like sculpting from marble, start with the big shapes. "In plein air painting," Archer adds, "I squint to eliminate detail and sketch big chunks of color and value [light and dark areas]. I ensure they work together before adding detail."

As you work through the broader composition, be open to sudden inspirations for details. These elements will add personality and depth to your work, such as a character's feline personality reflected in their facial proportions.

Key Takeaways and Conclusion

Essential Elements of Appeal

- Universal Recognition: Appeal draws viewers in instinctively

- Beyond Beauty: Appeal works for both beautiful and unsettling subjects

- Natural Foundations: Effective art builds on natural patterns

- Balance and Harmony: Combine familiar elements with fresh perspectives

Character and Context

- Unified Development: Create characters and environments together

- Emotional Depth: Let environments reflect character growth

- Cultural Authenticity: Research enriches your creative world

- Holistic Design: Every element should serve the story

Practical Approaches

- Start Big: Begin with basic shapes before details

- Natural Inspiration: Let nature guide your design choices

- Observational Practice: Develop your artistic eye through study

- Progressive Detail: Work methodically from general to specific

Professional Tips

- Use basic shapes as your foundation

- Let environments evolve with characters

- Research thoroughly for authenticity

- Trust your developing instincts

- Learn from nature's design principles

- Build complexity gradually

Final Thoughts

Appeal bridges the gap between your art and your audience, transforming basic shapes into resonant creations. Whether you're sketching for pleasure or pursuing professional artistry, understanding appeal launches your creative journey. Success comes through careful observation, consistent practice, and the thoughtful blend of technical skill with creative intuition.

Let’s Get Creative Together

If you're ready to embark on your creative journey, consider starting with a free consultation with a Creative Solutions Specialist. They can provide personalized guidance to help you achieve your artistic goals.